THIS REVIEW IS CERTIFIED SPOILER FREE

So, two years ago, pandemic gripped the land, and that’s an ironic statement because I mean the real one and not the board game. Yes, I know, I’m a comedic genius. During that time my friend’s and I turned to TableTop Simulator for our board game fix, something we’d only really dabbled with before (or since, come to think of it). As part of this we sought out a few games that none of us had physical copies for and after only a small amount of bickering we were convinced to try out The King’s Dilemma. The King’s Dilemma had the benefit of not only being highly rated but also a legacy game which seemed perfect given that there were five of us stuck inside 24/7 and we wanted to play board games somehow. So, having some kind of thing we could keep coming back to would surely only be beneficial!

In The King’s Dilemma you take on the role of one of 12 different noble houses in a fantasy kingdom, in a board game developed (shockingly) by the same guys who made Railroad Ink (shocking only in terms of what a side-step the game is). Across each game, you will continue to play as different generations of the same aristocratic house, with your group acting as councillors of the Kingdom of Ankist, a kingdom in in which the King himself really has very little power whatsoever…

Each game essentially represents the passing of generations, with a different King as the figurehead each time (decided by the winner of the previous game). Each game session plays out over a series of rounds where a card is drawn from the dilemma deck, with players then voting “Aye” or “Nay” on the dilemma of the hour (or abstaining as the case may be). The outcome of each dilemma then results in some of the five markers used to measure prosperity in the Kingdom going up or down. Agreeing with the generals to recruit more soldiers into the army causes a nice bump of three points for the Kingdom’s influence, but a downward turn of the people’s morale as they are conscripted.

If at any point during the game the cumulative stability of these five markers (representing influence, welfare, knowledge, morale and wealth) gets too high or too low, this results in the game’s end as the King either overturns his council or he abdicates in shame respectively. Alternatively, if a balancing act is played for long enough then the King may simply die of old age, again causing the end of the game.

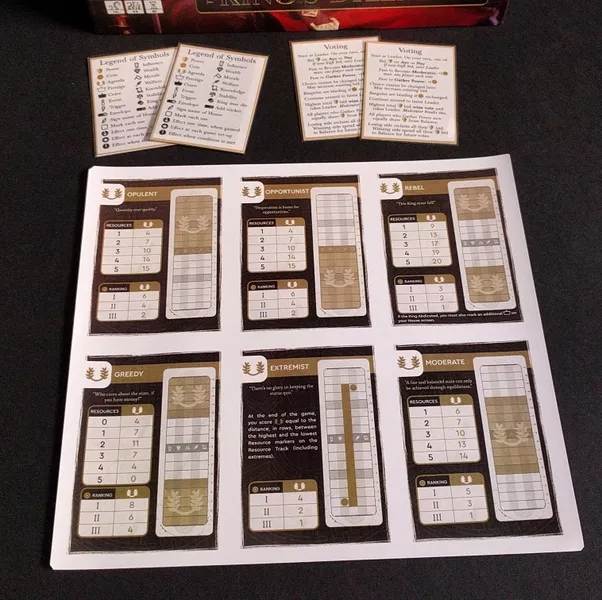

Each player drafts a card from a small deck at the start of each round which tells them where they want the markers to be on the stability track, with more markers in their zones meaning more points for them at the end of the game. Players also gain points for having more money, one of two currencies in the game. The other currency is power, which is used to represent political influence and is used for voting on the dilemmas while money is almost exclusively used purely for bribing other players.

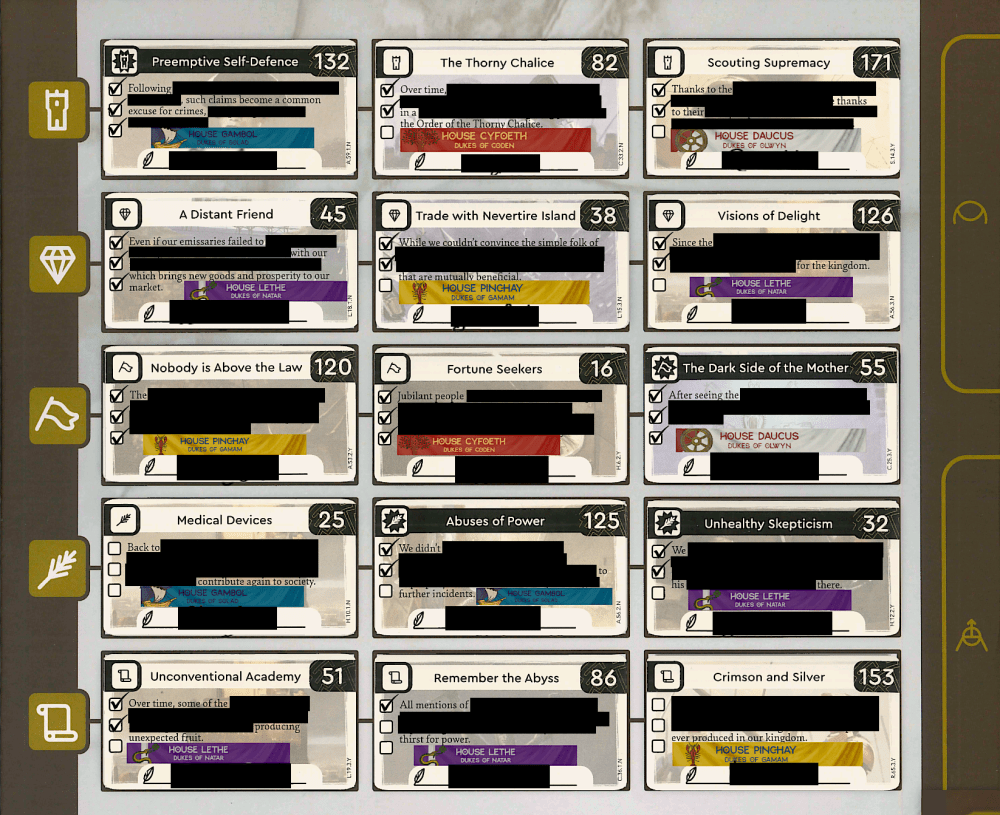

Lastly then are the game’s legacy elements. Each dilemma is a one-shot card and while the results, of conscripting the populace may cause the raising of the country’s influence, it also may result in opening one of 75 different card packs, introducing more dilemmas into the deck and thus weaving a stunningly branching narrative across multiple different storylines.

Alternatively, the game may ask you to place one of 177 stickers at the top of your board and sign it, representing the lasting consequences made by your house in a particular dilemma. Sure we have more soldiers in the army, but now the populace is constantly aware that your house cares more for swords and shields than it does for their well-being and so in each subsequent game you personally will have the added objective of trying to deal with this negative opinion of the people with an “open agenda” where if once more a game ends with morale in the dumps you lose points as the people further scorn your attitude. Or alternatively if it ends up high, then you gain extra points due to the people’s awareness that you went against your own tarnished reputation.

Mechanically then the game really is extraordinarily simple. You’re trying to juggle having enough power to get the varying tokens where you want on the board by voting correctly in different dilemmas. You want to try to influence the other players to vote your way, paying with money or favours, while also hoarding money for points at the end. You also want to try and bluff and threaten other councillors in mind games to prevent them from putting too much power into something you care about or making them accidentally spend way too on something you really don’t.

However, where the heart of the game truly lies is in its story. Playing out over approximately 15 sessions, you are experiencing the story of a Kingdom as it happens. Some dilemmas are delightfully small and local such as decisions over funding a concert or punishing a man for a crime, while others are far-reaching and grand involving war, famine and crazy fucking heretical witch cults…

Each dilemma is a self-contained little piece of lore, some of which have very long legacy consequences for the game, and yet remain bite-sized and easily digestible, but then on the whole you will find yourself considering massive story arcs and looking back through the decisions you made to realise how it came to this.

The game is also quite simply great fun because, as it is a board game with POINTS to be won, each councillor really mostly cares about the sliders and moving them where he wants them to be. Therefore, it doesn’t matter that the current dilemma is asking whether or not we should give the poor a piece of bread or whether we should stick them into work camps and feed them their children’s hearts, causing untold misery and suffering. What’s more important is that we get a bit more money in the kingdom and get that token HIGHER! So that’ll be an extra dose of suffering for me please! And so, naturally, given that you debate out each dilemma, this then means having to justify often quite outrageously slimy and disgusting things (to much hilarity).

Also, the dilemmas are often actually surprisingly morally complicated, meaning that just debating them on their own merit is entertaining and interesting enough, let alone when someone is blatantly pushing for the option that is GENUINELY evil. There are also regularly far-reaching consequences in terms of the decisions made each game, as every house has its own mini-objectives to fulfil over the course of numerous games, including even several massive ones which we have actually yet to discover in our own story.

For, while victory during each individual game of The King’s Dilemma is to be savoured, it is largely inconsequential next to the broader consequences of the realm itself! Sure, you may have won the right to name the next King, but perhaps at the expense of the longer-term stability. And over the course of multiple games, your position within each round actually determines whether you are awarded with Prestige or Crave points.

Now, again, we have yet to actually finish The King’s Dilemma, but it seems obvious from our current position that at the end of the campaign, if the Kingdom collapses, the person with the most Crave will win, whereas if the Kingdom survives or even (somehow) prospers, then it will be the person with the most overall Prestige… However, there is a lot of coy winking going on in the rules to suggest that it might not be QUITE so simple.

This also however means that as the campaign progresses houses start to devolve into political camps. Those with the most crave begin trying to push for worse outcomes and decisions, knowing that their long-term victory will stem only from the destruction of everything around them. Meanwhile others hoarding prestige will seek to genuinely improve the Kingdom’s standing and fortunes, because that will only mean improving their own. In short: the game actually makes you care. Not just about each of the storylines within the game, although that happens as well, but also about the Kingdom itself. Whether you care positively or negatively isn’t strictly important, but you do quite simply care about what happens.

It does help of course that that the storylines themselves are actually marvellous, with particular stories potentially going quiet for a while until a new dilemma pops up in the chain to a chorus of “oh god, we’re having to deal with these people… AGAIN!” Once more it comes back to that element of caring, of becoming invested. It becomes simply important to you what happens to your family and their fortunes within this kingdom. Which again, is amusing because really, even if you do things which are beneficial for the Kingdom, in reality you are only doing that because it benefits YOU in the moment.

There’s also so much character that has been worked into the game which is particularly true for each of the 12 possible houses, and that only serves the game’s purpose where you feel yourself stepping into the role of the elegant but arrogant artisans of Gamam or the debaucherous but happy-go-lucky impoverished of Allwed.

So, it should be clear, I like The King’s Dilemma. This is the sort of game which suits me, where the narrative really drives the fun and becoming invested in your house and the kingdom is what makes it a joy to play and to eagerly seek out what happens next.

However, this is not the case for those within my group, or specifically at least: Tim. My group is a very mechanically minded group, this is true both in video games and board games. In roleplaying video games they will skip dialogue, cut-scenes and make decisions based on amusement all in favour of reaching the next fight where the fun is then derived from overcoming the challenge, kicking ass and solving the puzzle in order to achieve victory.

Yes… That did make playing Divinity 2 with them a bit challenging at times…

This then also translates over into board games too. Some of the group favourites are those nitty-gritty engine-building games where it is all about squeezing the most value out of every card and token in order to build an unstoppable deck that crushes your opponents.

For these people, The King’s Dilemma simply falls flat. If it were a more social game, then people would perhaps have their minds changed by arguments, but 9 times out of 10 players will go into a vote with their mind absolutely made up on how they will vote. This makes the debate step largely a formality, done by those of us invested in the story to keep things going.

In practice one could play literally every dilemma like a round of poker, merely reading out the card and then placing your vote and power and bluffing and hedging with the other players, not really engaging with the actual dilemma itself. This is extremely frustrating then if you want something deep mechanically and you don’t even really have the option of changing people’s minds with quick thinking or presenting some strategy.

Another complaint, which I actually personally agree with, is that the use of the Chronicle stickers, while initially a novelty, really have significantly less impact upon the game than it promises. Not only does it really not impact the gameplay much, only barely, but they actually have less impact on the broader story as well.

I would have loved to see outcomes of dilemmas having varying and possibly hidden effects based on the presence of different stickers. For example, maybe the conscription of the populace is terrible for their morale, but actually your Great-Grandfather put in place a policy of hiring generals based on competence and not nobility, and so the lost value of the morale is actually halved two generations down the line.

Of course, I appreciate that this would be an absolute nightmare to balance across all the different stories, but at present it means that these stickers often simply do not have the impact that one feels they should. As a real example: early on you get a sticker introducing new, more drought-resistant crops to the Kingdom, and when you sign your name on that you are secure in the knowledge that this will never come up again… Even when other dilemmas arise talking about famine throughout the Kingdom.

I also feel that, unfortunately, we perhaps were a little unlucky in terms of some of our individual games which has resulted in the fact that actually most of our group is fairly balanced on both crave and prestige (hilariously, even the guy who was going for crave from the outset ended up with a totally balanced score sheet). Meaning that no real political camps have been drawn up even by game 10 because everyone is still uncertain where they’ll stand on EITHER leaderboard.

The game also has the slight issue that very occasionally it is possible to feel quite hard-done by. Specifically, again, we actually failed Tim’s house primary objective and so, knowing that there is now absolutely no way to achieve that has, very obviously, somewhat soured the desire to continue playing. The long and short of it is that from a mechanical and individual game perspective, honestly The King’s Dilemma is really not that great. It’s a game where the comparison to roleplaying actually feels somewhat apt, where you get out what you put in. And if you and your group are not the sort to really engage whole-heartedly with a make-believe story and the characters you embody, then likely you too will find the game uninteresting, shallow as a puddle and broadly frustrating to experience.

I will provide one final addendum to the above: it is worth remembering that we played an online and virtual version of the game and I find that it is often the case with these sorts of more “social” games that something is lost in playing through a screen. Perhaps the boys would have enjoyed it more in person?

And if you want to see some of those videos they can be found at the bottom of this post!

Gameplay: 3/10

Dead, dead simple to play, teach and experience. Unfortunately, however quite divisive. If you are narratively minded, each game will be exciting and a cause for constant discussion. However, from a more focused, mechanical perspective it is uninteresting, shallow and annoying.

Looks/Feel: 8/10 (kinda/sorta)

As we played via TTS it is impossible to really give a fair rating here as I never handled a physical component. However, I will say, the card art is fucking smashing, and that I personally constantly felt like a councillor from Game of Thrones, jockeying for position and glory within the fictional Kingdom.

Content: 10/10

OH. MY. DAYS. There’s just so many options and possibilities and avenues this game can take. Truly the actual story aspect of it and the depth of that is incredible, and there can be no denying it. Very, very reasonably priced too.

Replayability: 9/10

While “replay” is the wrong choice of words as you will never be able to “replay” the campaign itself, each individual new game is fabulous thanks to the evolving story, and means you are constantly wanting to keep coming back to it. A limited run of ~15 sessions is a lot more than I think most get out of most games.

Social Score: 8/10

The arguing and bickering over each dilemma never ceased being amusing for me, particularly when trying to justify outright atrocities. But also, taking on the role of individual houses and watching everyone else develop as “characters” over multiple sessions really is just extremely amusing to experience.